I teach at-risk kids. It’s mostly a good job. The kids are mostly good. Even when they’re bad, they usually aren’t that bad to me. Had I written this in September when I had the worst class I’ve ever taught, I might have sounded different, but that’s why you should never listen to a teacher vent their spleen. It’s April and, as a friend used to say all year round, “it’s almost June!” I’m calmer now, have the classroom running well, and it might now be worth listening to me talk about what happens when a kid loses control in school. That’s what happened today. It didn’t happen to me or in my classroom, but I heard it and got to thinking.

The kid in question is volatile. That’s a nicer description of him than I’d have used in September. I’ve grown to enjoy the kid, whom I’ll call Frank, and we have found ways to work together. Frank says most of whatever is on his mind at any moment and has been taught that it’s endearing to be negative, nasty, and foul-mouthed. I’m not making fun of him or embellishing here. He really does think this is the way to be and he is very confused and upset when it goes poorly for him. An example from this morning’s class with him might help.

Frank came back to school after almost a week of skipping. I was genuinely happy to see him, but rather than squeal or carry on (you’d be surprised how many people do that to a kid already feeling weird about coming back to school and how destructive it is), I said, “hey, Frank, good to see you this morning.” I said it calmly and with only the hint of a smile and a nod of my head. I knew before he spoke how he would reply. Frank said, “well, it fucking sucks to be here.” This is Frank.

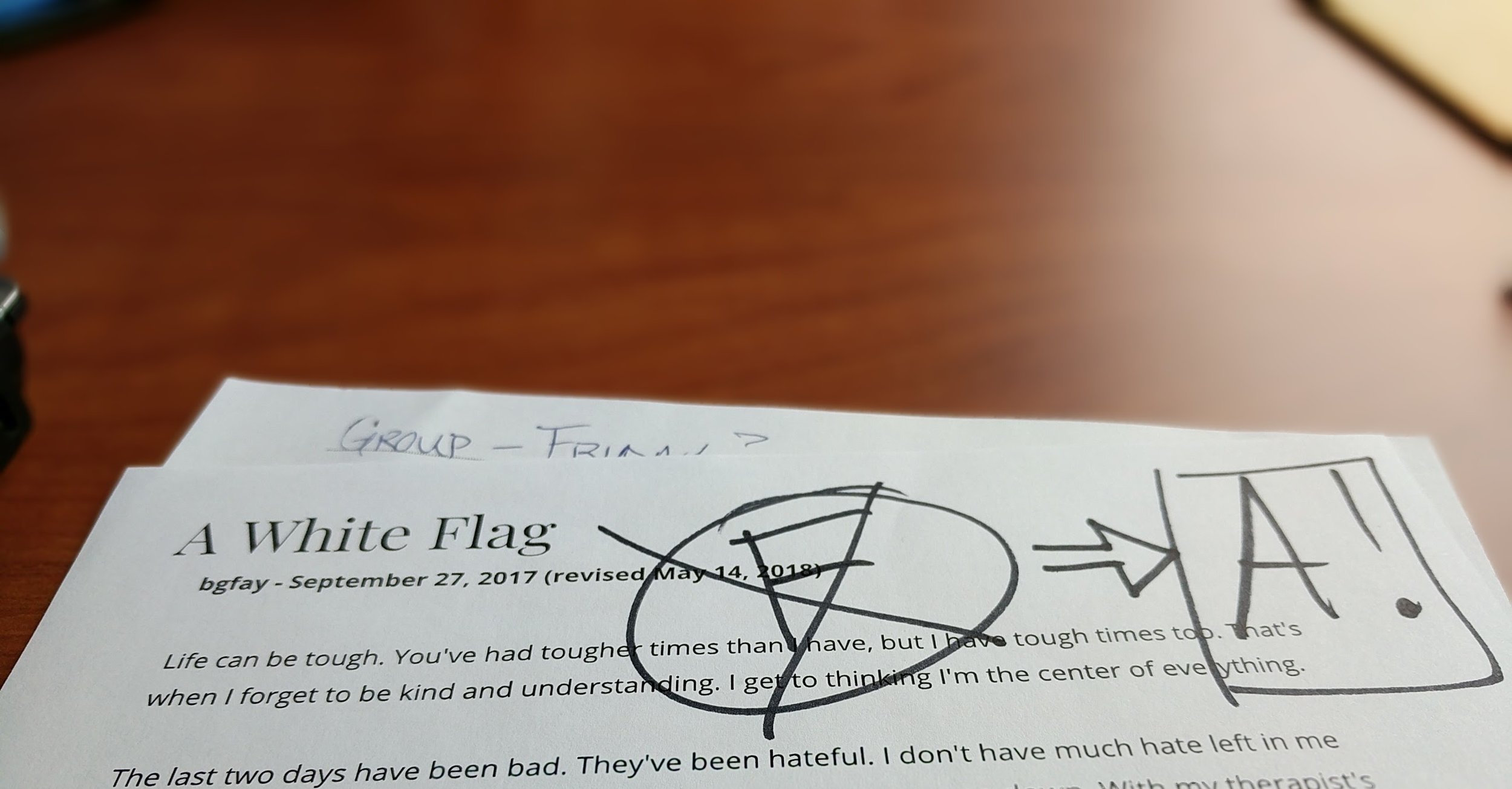

This is me. I nodded twice at him, paused, and said, “yeah, but I’m glad to see you and isn’t what I feel all that really matters here?” Frank smiled at that. “You’re a crackhead, Brian,” he said. I shrugged and we went from there. The hour went well. Frank really does believe that he’s being friendly or funny when he says these things. While it can be a bit of a drain, I’ve learned to take his comments and mannerisms as a kind of friendliness or at least an attempt at it. It turns out that calling me a crackhead and letting me get away with my joke about me being the one who matters is Frank showing me respect. It only took me five months to figure that out.

Three hours later I heard Frank telling another teacher to go fuck himself. The exact words were, “fuck you, fuck, you, fuck you; I don’t have to do a fucking thing you fucking tell me to, you fucking asshole piece of shit!” (semicolon mine). This was a whole other thing than mine and Frank’s morning greeting. He was screaming all this loud enough to be heard all the way down the hall. It’s important to remember all that yelling when I get around to thinking about what Frank was trying to do in all this, but before I go there, let’s hear from the teacher who said everything you would expect him to say. It turns out that everything you expect is all wrong.

The teacher said, “You can’t talk to me like that!” Frank kept right on talking how he wanted to. The teacher asked, “What did you say?” after Frank swore at him and so Frank swore at him even louder. The teacher moved on to saying, “Stop talking! Stop Talking! Stop Talking!” and “Stop shouting and calm down! You’re out of control!” It went on like that. I was in my room thinking of the last time someone yelled at me to calm down and remembering how well that went.

Since I’ve said these were the wrong responses, what are the right ones? I’ll get to those after answering a more pressing question which is why I didn’t go help calm the situation. There are two answers to that. One, I’ve tried to help these two before and it hasn’t gone well, for me or for them. They need to find some way through this. And two, I was curious how it would play out. I had my bet as to how it would go and would have put down most of my savings on that bet, but I wanted to see for sure. Would it be awful to admit that I also sometimes enjoy the show?

Back to the right responses. The teacher could have begun with silence. It’s a good start but might be the hardest thing to do. When Frank came at me this morning, I nodded but otherwise held still. I stayed silent for a moment and let his comment be there. I didn’t address it as good or bad. I didn’t react to it because I’ve had enough experience with him to know better. I gave it a moment. I gave him a moment. I gave me a moment. Then I came back with a stupid joke that wasn’t made at his expense. If I make fun of him in that moment, then he should tell me to go fuck off. I would deserve it. But my joke was just a light thing made at my expense in which I claim that I’m the most important (sometimes the most beautiful or talented or whatever) person in the room. It’s mocking me, not him. Everything I did and said was meant to take all the heat out of his comment and move us into a different space. His comments are pushes. The decision that teacher and I have to make is whether or not to push back. It’s hard not to push back, but it’s worth it to become a ghost.

That’s what I call it: becoming a ghost, because it’s really tough to push a ghost around. Mostly when someone tries, they go right through. After a time they give up. Also, ghosts are strong and take care of themselves (except maybe on Scooby Doo). They can haunt someone long enough to have an influence. Kids challenge me pretty regularly and I’m not always able to become a ghost, but each time I do, the conflict ends fast. I don’t win the conflict or lose it. Instead, the conflict loses us.

Being a ghost could go like this: Frank is out in the hall screaming at the teacher: “fuck you, fuck, you, fuck you; I don’t have to do a fucking thing you fucking tell me to, you fucking asshole piece of shit!” This time, the teacher says nothing for a moment. He counts to four. He nods. “Okay,” he says. And here’s where it could get interesting. The teacher could say, quietly, “you know what? You’re right. You don’t have to do anything I tell you.” If I’m that teacher, I wait another moment to set up one of these two jokes:

Aren’t all pieces of shit asshole pieces?

Mom was going to name me Fucking Asshole Piece Of Shit, but couldn’t fit it on the birth certificate.

Though both of those jokes are pure gold, it’s probably best I wasn’t in the hall and just whispered them to my amused self. I’m ever so clever.

If Frank calms down even just a little, the teacher can say, “I’m going to step away for a minute, okay? Because you don’t want to be looking at or listening to me right now, right?” Phrased as questions, these give Frank the power to choose. He’s been after that power all along. That’s why he has been yelling loud enough to hear it up and down the hall. Frank is just a kid. He comes from a tough family, a tough history. He’s used to being ignored until he sets his hair on fire and breaks every window. He wants a modicum of control in this life and giving it to him feels impossible when he’s screaming, but it works almost every time.

I imagine you’re thinking, “but he gets away with all this swearing and screaming without any consequence!” Maybe he does, but maybe getting away with it isn’t an accurate picture of what’s happening. Why not? Because he wasn’t the only one who started the conflict. That takes two. Frank was being Frank, a teenage kid in a school for at-risk students, with whatever problems he brought with him from home (or wherever else he is living) this morning. Getting away with this would mean the teacher has to lose something. I”m suggesting that the teacher take losing entirely out of the situation and become a ghost. When that happens, there’s nothing to get away with, no win (or loss) to be had. The ghost teacher loses nothing and gains some peace, the kid gets to have some control and calms down. and we all move forward with the day a lot easier than after a battle.

It’s that or the teacher has to tell the kid to fuck off. I mean, that’s basically what we’re saying when we engage in conflict. Fuck you, kid, you’re suspended! Fuck you, I’m in charge! Fuck you, fuck you, and fuck you until you stop telling me to fuck off!

The Almost-June friend I quoted at the top used to say, “the kid isn’t mad at you, he’s mad near you.” Frank was mad today and something set off the anger he had built up. When a bomb goes off, it doesn’t target certain people. It just blows away anyone in range. Frank does too. Bombs though don’t have to go off. Even if the fuse is lit, it can be snuffed out or deprived of its oxygen. It’s no fun to be told to fuck off. It’s no fun to be yelled at. And when these things happen, the natural reaction is to fight back. I’ve been at this teaching thing for almost twenty five years and I’m just learning to go against that natural inclination. I come out of it a crackhead, but my jokes at least make me laugh. And we go on with our days.